Another annual sun has now set, and of books that came to life within this year-span, there are a few that are worth looking back to, anew. In the Assamese literary space, both in the vernacular and in translation, writings in different genres have enriched our understanding in their distinctive ways. Short fiction, for example, saw some outstanding contributions. In Pita-Pu tra, Bhupendranarayan Bhattacharyya has given us a sumptuously rich gathering of tales which cover life-slices in their striking individuality. Bats and Bananas is one story in this collection that captures the deeply embedded localised tongue of Nalbari, nuancing the ambience by a notice able atmospheric feel. Often, transference of the spoken onto the space of the published page can bring forth unwieldy challenges. Bhattacharyya eases past them with the command of an accomplished storyteller: In Cleopatra, he places the templates of art and life within the space of performance where we see tweaking of another kind: What is staged can also hold the mirror for the shadows that remain out of sight.

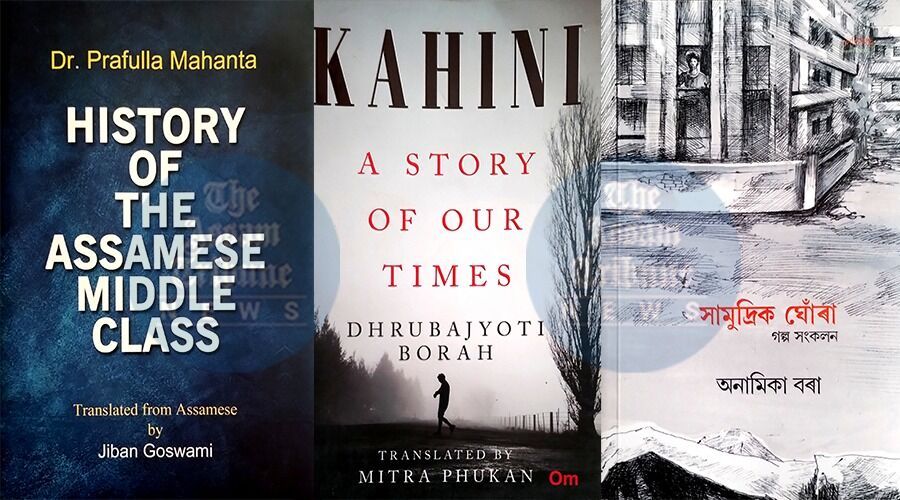

Samudrik Ghora, Anamika Bora's book of short fiction, takes us to spaces of the familiar, but with a compelling craftsmanship that converses with the unacknowledged patterns of existence. Bora's stories have that quietly attractive poise of prose, for in her word choices the very mundane becomes graphically visible. The situations are evidently run-of-the-mill, but the narratives are markedly animated by her representation of carefully etched realities. In The Pain of Narcissus, a broken world whose fragments are too widespread to reassemble, is presented with compassionate concern. The gap between the spoken and the unstated is drawn on a canvas where the various social forces intersect conflictual. The story speaks of an anchored play of friendship where the moral centre keeps shifting even as the ache lingers without finding a voice. Bora has written of support structures that hinge on the margins of troubled spaces, the social grammar there often remaining fringe fully unstitched. This is one aspect of her narratives in Samudrik Ghora that strikingly stands out as a characteristic feature.

Dhrubajyoti Borah's Kahini, whose English translation has come out this year, is an engagingly told narrative that connects us to the enticing architectonics of the Assamese story telling tradition. In drawing creative sustenance from another landmark in modern Assamese fiction, Oxanto Electron by Saurav Kumar Chaliha, Kahini recreates the twenty-first century milieu by attending to the repository of social angst by a brilliant assemblage of images. The narrative coalesces the struggling antipathies that run through the generational priorities onto the same situational plane, not for effect, but for social assessment. Kahini adopts the mould of the 'story' frame for another significant reason: it aspires to present the time-specific contemporaneity through the register of a familial bond, that of a grandfather and his grandson. As locations change, so does the backdrop, yet the invested emotions are too deep-rooted to be disengaged from the individual spaces that make the people who they are. Mitra Phukan places things in context in her "Introduction to Kahini as its translator: "As the main characters, the grandfather and the grandson move through the story, we come across vignettes of many social realities of the day. In a way, it is, loosely, a kind of picaresque novel, with the two protagonists moving from one adventure to another. These mirror what has happened, is still happening, all around us. It shows the power of money but also the freedom that comes from not being a slave to it.

Yatra: An Unfinished Novel has the tunnelling characteristic of interwoven movements, not merely of the physical kind, but also such that bear their own ruminatory logic. The English translation of Harekrishna Deka's fictional narrative is an important publication this year. Covering an extensively charted ambit where questions of indigeneity run against the brickwall of 'progress', Yatra can be seen as a convergence where the tethered melange of threaded stories meet voices from the periphery. The ambiguous placement of crisscrossed pathways comes through as that modicum of uncertainty which hovers over the civilizational question without annotation in the novel. As the narrator says: "Each of us are in our different journeys. If your journey was precarious, so was mine. What happened to me after corning here, I could not have envisioned. But, you ought not to have taken me for granted if you knew your own ways.”

The publication of Prafulla Mahanta's History of the Assamese Middle Class in English translation is an assured enhancement of our intellectual library. At a time when the very fabric of our society is facing a churning, wrought both from within and beyond, this book will provide a timely frame for us to revisit the circumstances in which a major segment of the Assamese cultural ethos sought its mooring. Archival rich, and contextually attentive to the changing dimensions of our societal flow. History of the Assamese Middle Class is an informative and necessary work of our time. The textured layers thot have gone into shaping the cultural tonalities of the people, complex as they are, find through Mahanta's observant eye a sustained analytical look.

Anubhav Tulasi's Janajakhini expands the poetic horizons of contemporary Assamese verse by addressing questions of articulation and word-coordination in a space where his metier is well established. Poems which seek to recalibrate the known ensembles of sociality vitalise the pages of this book. In Sananta Tanti's Last Wish, we find the following words, words that compel us to wonder at the limiting succour of companionship, which too is pretty short-lived: "How am I to look at /that's what I wanted to know of the high street wall/but didn't/How am I to look at/that's what I wanted to know from the watery-mirrors the potholes were/ but didn't. Telling commentary on the anguish even whose surface is unscratched.

The variety of books, especially in terms of the experiential adventures they have taken up to place in their pages, suggest promising times ahead of Assamese writing. The coming year will see these and other enterprising dimensions coming into the field, that we can surely hope for.

By Bibhash Choudhury