Petrol power might have quickly won over the market but it was steam that first powered buses and vans

Petrol power might have quickly won over the market but it was steam that first powered buses and vans

It would be reasonable to assume that motorised commercial vehicles came some time later than cars, considering how puny the very first cars were. Take the Benz Viktoria of 1893, for instance: its single cylinder put out just 3hp.

But you would be dead wrong: that very car was used to create the first combustion-engined bus in 1895 – the year of this magazine’s foundation – and shortly afterwards the first combustion-engined van.

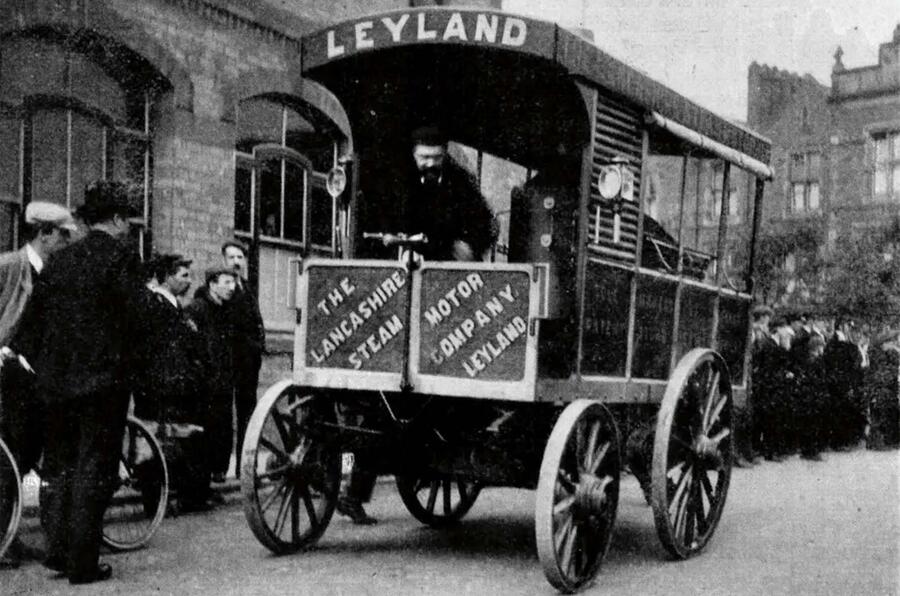

And we can go back even further, all the way to the 1830s, when the first steam-powered buses were tried (at about 12mph) in London.

“It is evident that steam and petroleum vans are coming into more and more extensive use, and a large number of orders for them are being given out,” commented Autocar no fewer than 129 years ago. “Tradespeople understand the value of these vehicles, not only for the speedy and economical delivery of goods, but also as an advertisement.”

We were reporting the news that a big department store in Paris, Grands Magasins du Louvre, had taken a petrol-engined Peugeot parcel van on trial, to see whether such vehicles might be more economical to run than its 200 carts and 500 horses – which were extremely expensive.

Just two months later, we relayed: “The vehicle weighs [610kg] in running order and will carry a load of [480kg] at a speed of 9mph. It is in continuous use from 8am to 7pm. Were it horsed, the teams would have to be changed every four hours.”

It’s no surprise, then, that within a year of these petrol vans being in operation, the price of a Louvre delivery had fallen from 70c to 7c. Another major advantage was that the removal of horses halved a vehicle’s length, in theory doubling a city’s traffic capacity.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com

“The streets in Paris are for the most part very narrow, and vans and buses take up so much space that the whole traffic is often at a standstill until these ungainly vehicles can extricate themselves. This would be certainly avoided if the traffic were much faster,” we noted.

Boiler power had started the race in pole position but fallen at the first hurdle, we explained: “Serpollet’s steam vans, constructed for [Paris clothes shop] La Belle Jardinière, were among the first to be used for the delivery of goods.

[However] the machinery occupied at least one-third of the vehicle, so that a great deal of valuable space had to be sacrificed – a matter of great importance to users who have to deliver enormous quantities of goods during the course of the day.”

Electric vans were also being developed, but it was found with disappointment that they could do only around 40 miles per charge.

Several steam buses were also operational in France. So novel and useful were they that Brits would book tours on them with travel agent Thomas Cook.

But again, there was the limitation of the mechanicals taking up much of the available space – and attitudes towards them weren’t helped by one exploding, killing a passenger.

Britain, meanwhile, continued with the development of electric buses. A large double-decker had been operational in London as far back as 1891, and in 1896 we reported on a new creation: “It has accommodation for 26 passengers and only weighs [2230kg].

"The storage batteries are a new pattern and weigh but [760kg]. These are adapted to be very easily removed and recharged, the battery power being sufficient to drive the bus over any of the ordinary routes.

"It takes no longer to replace an exhausted set of batteries than it does to effect a change of horses at the end of a stage. The batteries are so well insulated from vibration by the system of springs on which the vehicle is hung that we are assured no acid has ever been spilled.

"And, of course, the running of the motor is absolutely regular, and quite different from the comparatively spasmodic jerks of horses as they drag a vehicle along.”

Another benefit of a motorised bus was it being able to stop to pick up passengers. Horse-drawn ones made you board while still moving.

Petrol power may have quickly won over the van market, but the immense strength of steam power meant that many buses continued to run on coke into the 1920s and large lorries well into the 1930s.