14 March 1933 – 3 November 2024

The musician salutes his friend, the virtuoso producer and composer and ‘a benevolent cheerleader for the wonder of music’

Of all the lessons I learned from Quincy, one that always stays with me is something I read in his memoir, Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones, a beautiful, unparalleled story of music, civil rights, family and generosity. He was in his mid-20s, already a celebrated musician and arranger for Ray Charles and Dinah Washington, and he walked away from it all, packed up and moved to Paris to study music theory and composition under Nadia Boulanger, the famous composer and mentor.

Imagine reaching the pinnacle of success, especially as a young Black musician in segregated 1950s America, and saying – and this is my own editorial humour, not a direct Quincy quote – thanks, but I’m starting over for the sake of chords and harmony. I fantasise about having that kind of courage. The guts to drop everything, leave the rat race and bury myself in theory and orchestration, and return a musical Jedi master, instead of freezing like a deer in headlights at Abbey Road while conductors toss around terms that may as well be in Klingon.

But that’s the peril of holding Quincy as a yardstick. He’s an impossible standard. For producers and arrangers like me, he didn’t just raise the bar; he hid it where no one could reach.

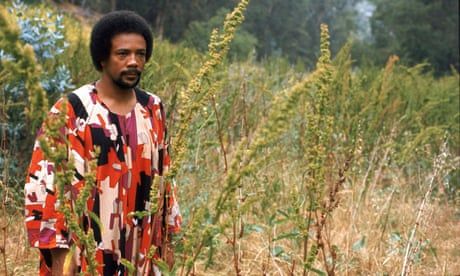

I was lucky enough to spend time with Quincy. I was once engaged to his daughter, Rashida, with whom I remain close to this day. Over the years, he would send me kind notes – he had a particular fondness for Amy [Winehouse] – and we’d often hang out whenever I played the Montreux jazz festival, his beloved stomping ground.

Seeing him there, stage right, seated in his director’s chair – looking every bit the debonair godfather of music, smiling back at you – elicited a wild mix of emotions. The greatest producer and arranger of all time, watching your every move, was utterly terrifying. And yet he only radiated generosity. All he wanted was for you to win, to shine. He had already achieved the unimaginable. Now he existed as something rare and beautiful – a benevolent cheerleader for the wonder of music itself.

A few years back, we worked together on a song for Rashida’s documentary about him, Quincy. Quincy arrived with the A-team in tow – his Off the Wall squad, no less. He was in his late 80s, quieter now, but the room still tilted towards him.

At one point, I got stuck on a trumpet solo – take after take, and I couldn’t put my finger on what was wrong. Quincy, silent all day, finally piped up: “Tell him to try a cup mute.” “Excuse me, Q?” He nodded. “Cup mute.” The trumpeter took out a cup mute, and just like that, the sound I’d been chasing appeared. Quincy knew – intuitively, spiritually – what I was searching for and what the song needed. He was a guru and musical maestro.