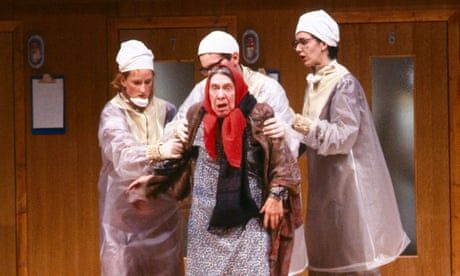

Vladimir Gubarev’s tragic satire about the response to the nuclear disaster transfixed audiences and showed the absolute necessity of theatre

I was pregnant when the terrifying radiation clouds came over Europe after the Chornobyl disaster. My interest was much greater as a result. I was at the Royal Shakespeare Company as a director at the time, and they had asked me to find a contemporary play for the next London season in 1987.

By coincidence, I got a phone call from Michael Glenny, the translator. He had come across this play being done in Russia. Most of its regional theatres had ensemble troupes and they were all doing it.

Vladimir Gubarev was the science editor of the newspaper Pravda and was one of the first journalists to step inside Chornobyl and witness what had happened. He was so horrified that he didn’t want to just write journalism. He’d never written a play before, but he went away to his dacha and wrote Sarcophagus. It dealt with what happened at the plant, but also touched on so many other things to do with corruption at the time in Russia. This was a moment when Gorbachev had announced perestroika. So you were kind of encouraged to be truthful about everything. The play talked about alcoholism, corruption, laziness. All the things which previously you wouldn’t have been able to speak about because the great Soviet empire was glorious and untouchable.

Chornobyl was a symptom of all of it. The sarcophagus was a literal thing, because the solution to trying to deal with the radiation was to enclose everything in a concrete bunker so the radiation couldn’t get out. And that’s what happened, although it is also a perfect metaphor for a totally sealed up country where the truth can’t get out.

Continue reading...