This political satire of insurrection and propaganda during the civil war, which is thought to have cost the author his life, gets an English translation at last

Oromay begins as it means to go on, at hurtling speed. A television journalist wakes late, with 20 minutes to catch a plane. And not just any plane: a plane carrying most of the leadership of Ethiopia. Tsegaye has hardly rubbed the sleep from his eyes when he finds himself in first class, receiving orders. There is to be an all-out push to bring the northern province of Eritrea into line with the revolution. He is in charge of hearts and minds, which must be changed. At once.

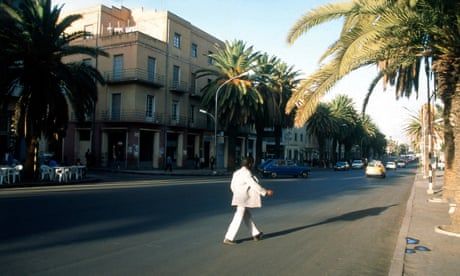

Oromay is set in the first months of 1982, seven years after emperor Haile Selassie was killed by a military junta led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, who by then had eliminated almost all opposition. A security agent in Oromay describes Eritrea immediately after the coup: beatings, jailings, extra-judicial killings, “corpses in the streets of Asmara almost every morning” – but this happened all across the country. A 1991 report from Human Rights Watch estimated that a minimum of 10,000 people died in Addis Ababa alone during the Red Terror from 1976 to 78; many more were imprisoned or fled. Those targeted were usually young, urban and educated, even if minimally. “That generation was lost,” the report reads, “with the remainder so cowed and terrified that any expression of dissent in Addis Ababa was unthinkable for a decade.” In Eritrea, which since it was colonised by Italy in the late 19th century had had a difficult and constantly shifting relationship with the Ethiopian capital, the repression had the effect of strengthening resistance. “We share,” says the security agent, “the blame for that” – but this time, he promises, it’s going to be different. With this new Red Star Campaign, two years in the planning, the promise of safety will be paramount. Though of course, “we do have to break the insurgency’s back”.

Continue reading...