When you attend your local choir or yoga class, just stop and think – where are the disabled adults?

In what passes for the national conversation, our social care crisis tends to be reduced to a handful of factors so familiar they now feel like cliches. Just about all of them are centred on older people, the pressures on financially broken local councils from an ageing society and people having to sell their homes to pay for residential care. All these things, of course, are urgent and hugely significant – but they exclude a huge part of society for whom care is just as important. The reason why that happens is not hard to work out: it reflects a set of ingrained, almost Victorian prejudices – and, without wanting to sound too melodramatic, the last frontier of the struggle for human rights.

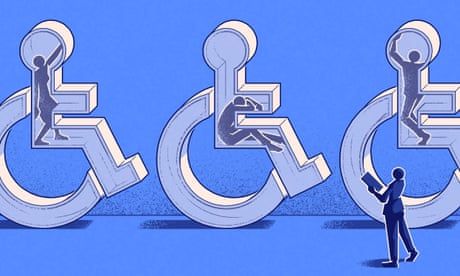

Just under 50% of care spending in England goes on support for disabled adults of working age, and more than two-thirds of that money is dedicated to people with learning disabilities. What this part of the social care picture has in common with help for older people is pretty clear: years of austerity, recruitment problems tied to low-paid jobs (made worse by Brexit), and the endless failures of successive governments to tackle a huge list of systemic problems. But the failings of care for disabled people have their own specifics: nonexistent local planning for the transition from childhood to life as an adult, no conception of successful grownup lives that does not involve paid work, and a national habit that is completely toxic: shutting away far too many disabled people, to the point where they simply cannot participate in society.

John Harris is a Guardian columnist. His memoir Maybe I’m Amazed, about his autistic son James and how music became their shared language, is published in March. For more information, visit maybeimamazed.substack.com

Continue reading...